Thomas Hanna was not simply the founder of the field of Somatics. Tom was a deeply contemplative, brilliant philosopher with an uncanny vision; however, most important to me, he was a wonderful father. This reflection on Tom is an attempt to shed some first-person perspective on what it was like to be raised in the Hanna family, how the inner person of Tom influenced his work, and how my personal relationship with my father shaped the person that I have now become as an adult.

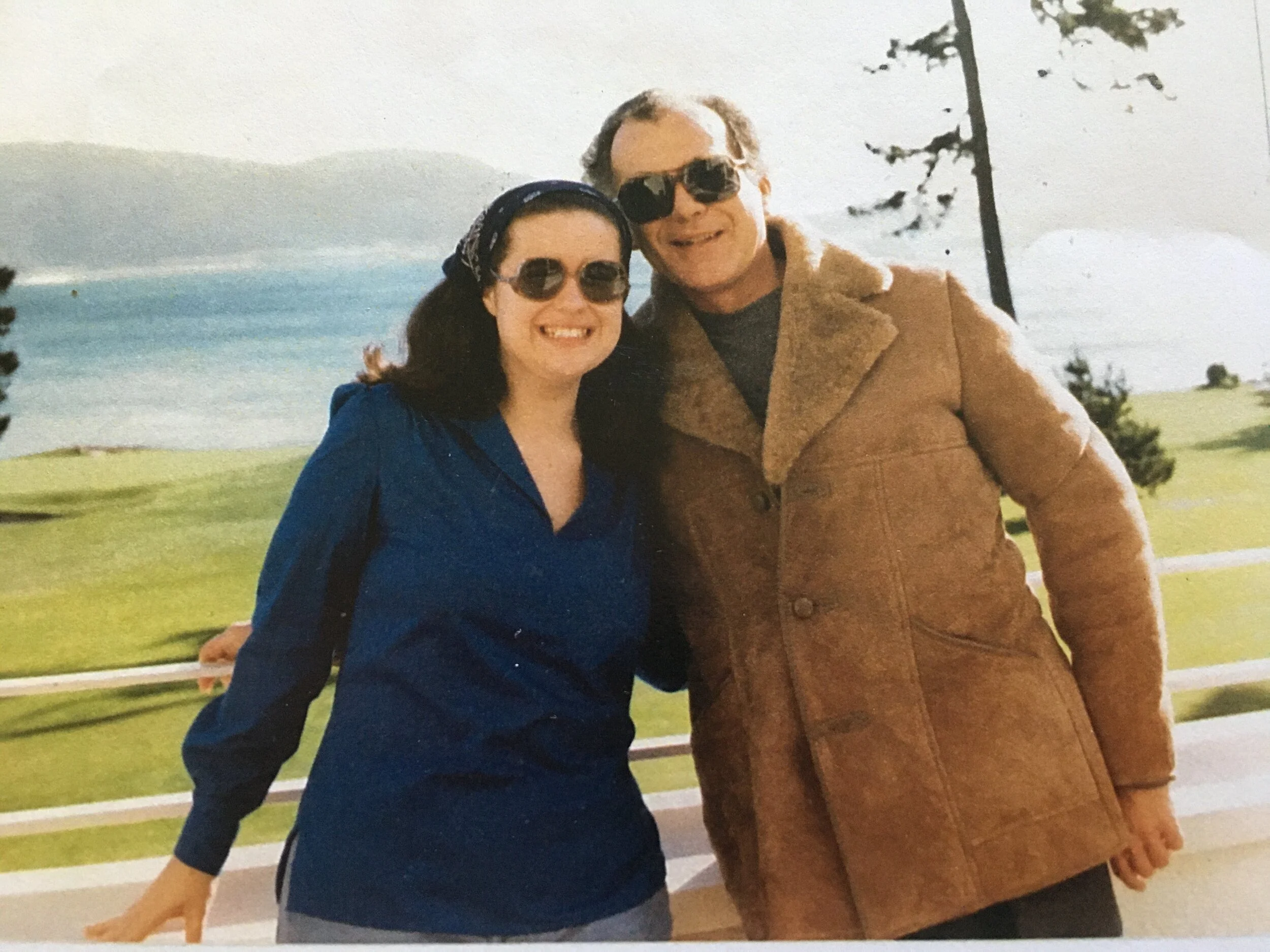

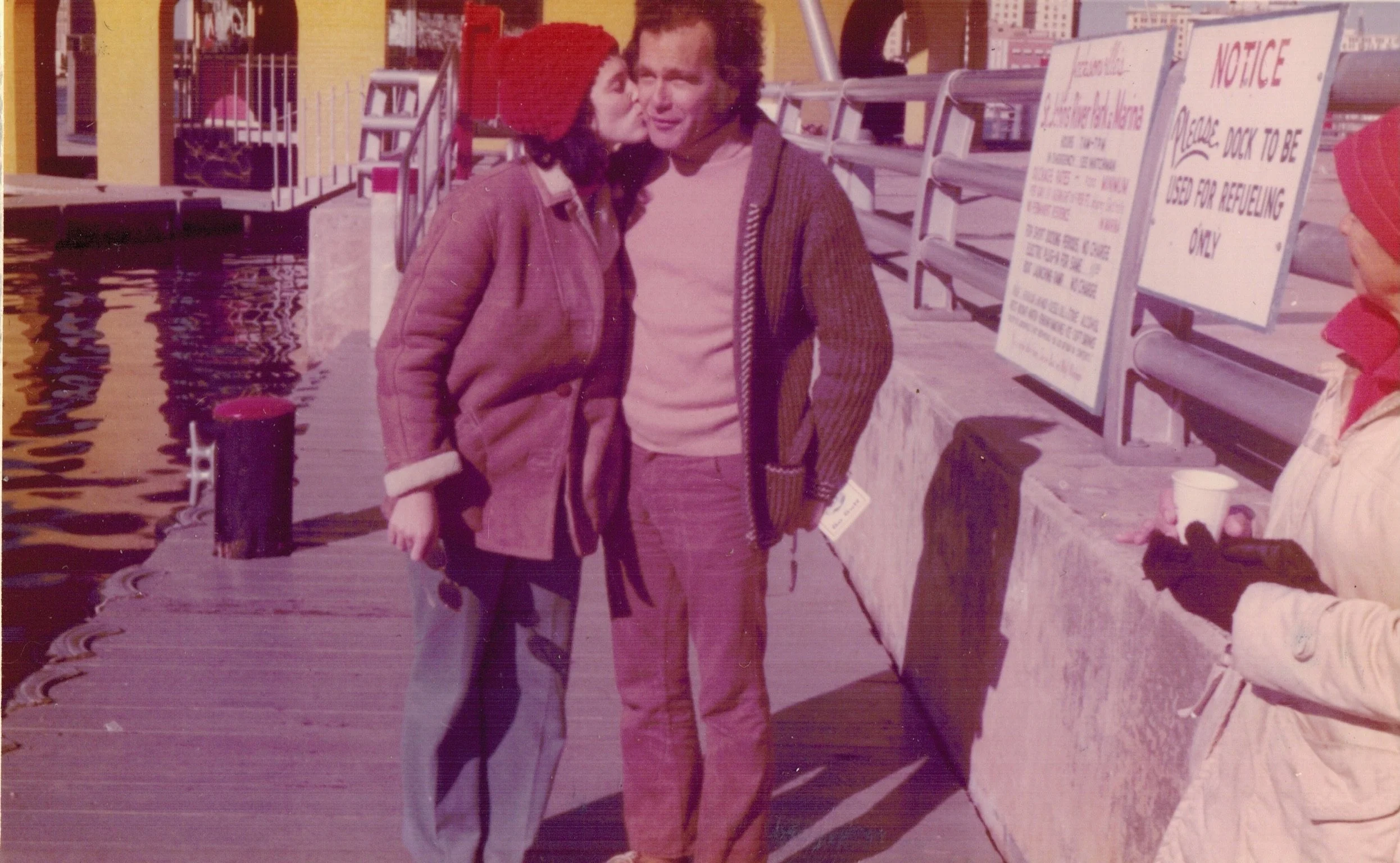

Tom and me, Pebble Beach, CA 1978

Tom the Contemplative

Tom contemplating in the backyard hammock. Gainesville Florida, mid 1960’s

Tom grew up in Waco, Texas- a fact of which he was not particularly proud. Tom felt little respect for the small minded, insular Middle American community where he was raised.

Tom with his mother visiting the family burial plot in Waco, Texas.

I do, however, remember a few positive stories he told about his childhood years. Tom often reminisced of walking to grade school while "smelling the wafting heat of the pavement after a sudden rain"; he talked fondly of talent shows he had performed in and of his glory days playing school football with his friend “Froggy” Williams. I don't remember much about Froggy except that Tom would always mention his name in such a way that I believe he must have been someone very important to him.

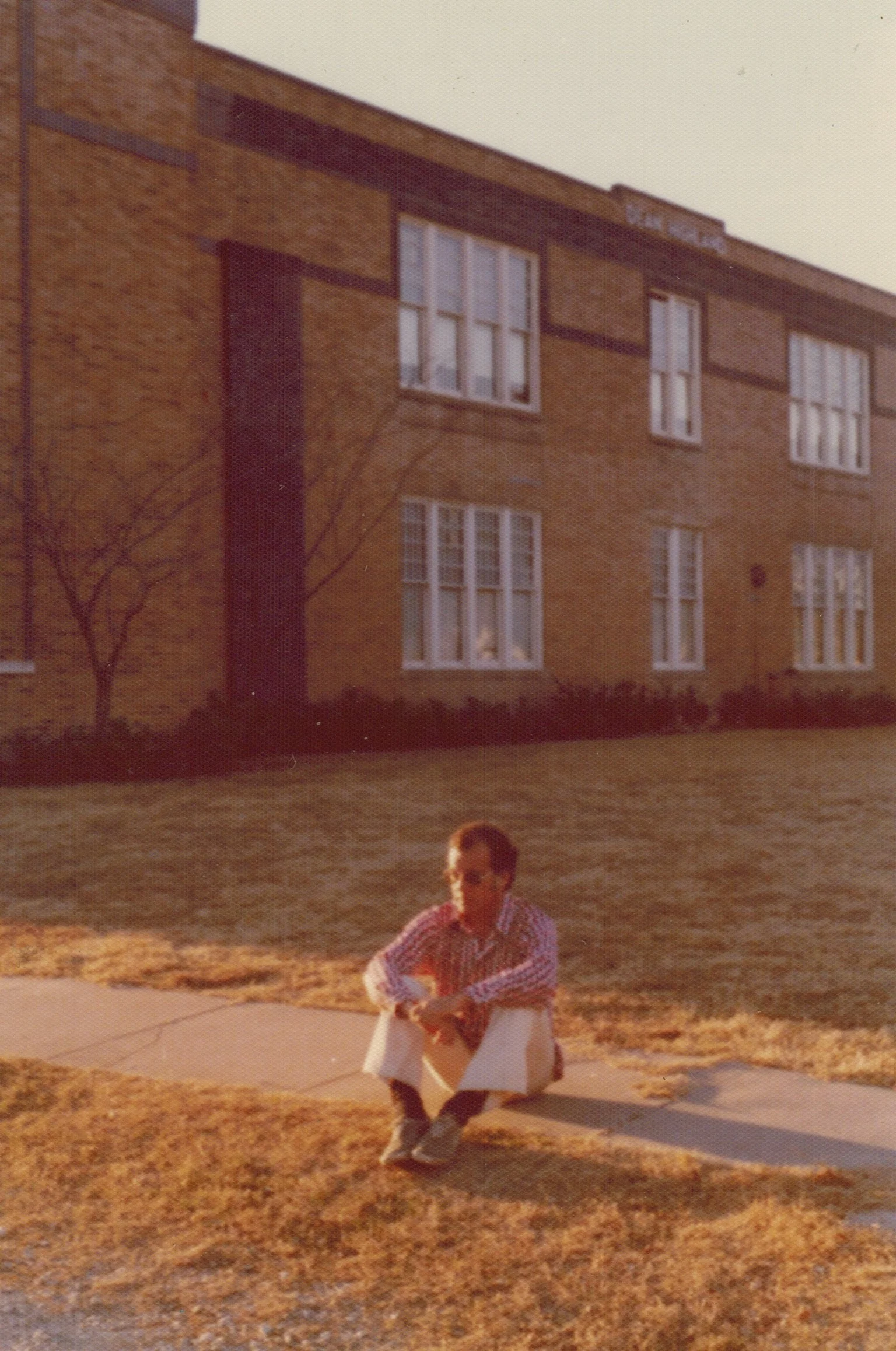

Tom posing outside his Waco, Texas Elementary School

I think that growing up in a Southern conservative town was formative for Tom in a way that influenced his later work. After high school, Tom decided to attend Texas Christian University to become a minister. The church was an important part of his early development and his subsequent work in the college ministry is where Tom honed much of his thoughtful nature and effusive communication skill. I believe that the part of Tom who continually questioned the nature of humanity, the meaning of life, and the significance of our place in the universe began with his initial religious quest.

Tom during his college undergrad years in Texas.

It was during college that my mother first met Tom at a social event where Tom was singing and playing guitar. My mother was mesmerized and asked, "Who is that fellow?" "Tommy Hanna," was the reply, "but don't get any ideas 'cause he has a girlfriend already." My mother did, however, have ideas and when my parents eventually got together, Tom was just about to complete his divinity degree. A big part of their relationship was intellectual and artistic in nature, and when not attending church activities, Tom would take my mother to the library to read great literature and listen to classical music together for hours. Frederick Delius was his favorite composer. During their courtship, my mother often asked Tom to explain why he so fervently believed the doctrine of the church. These discussions started a philosophical and intellectual fire that would burn for the rest of his life.

Susan Hanna in Texas during the college years when she met Tom Hanna.

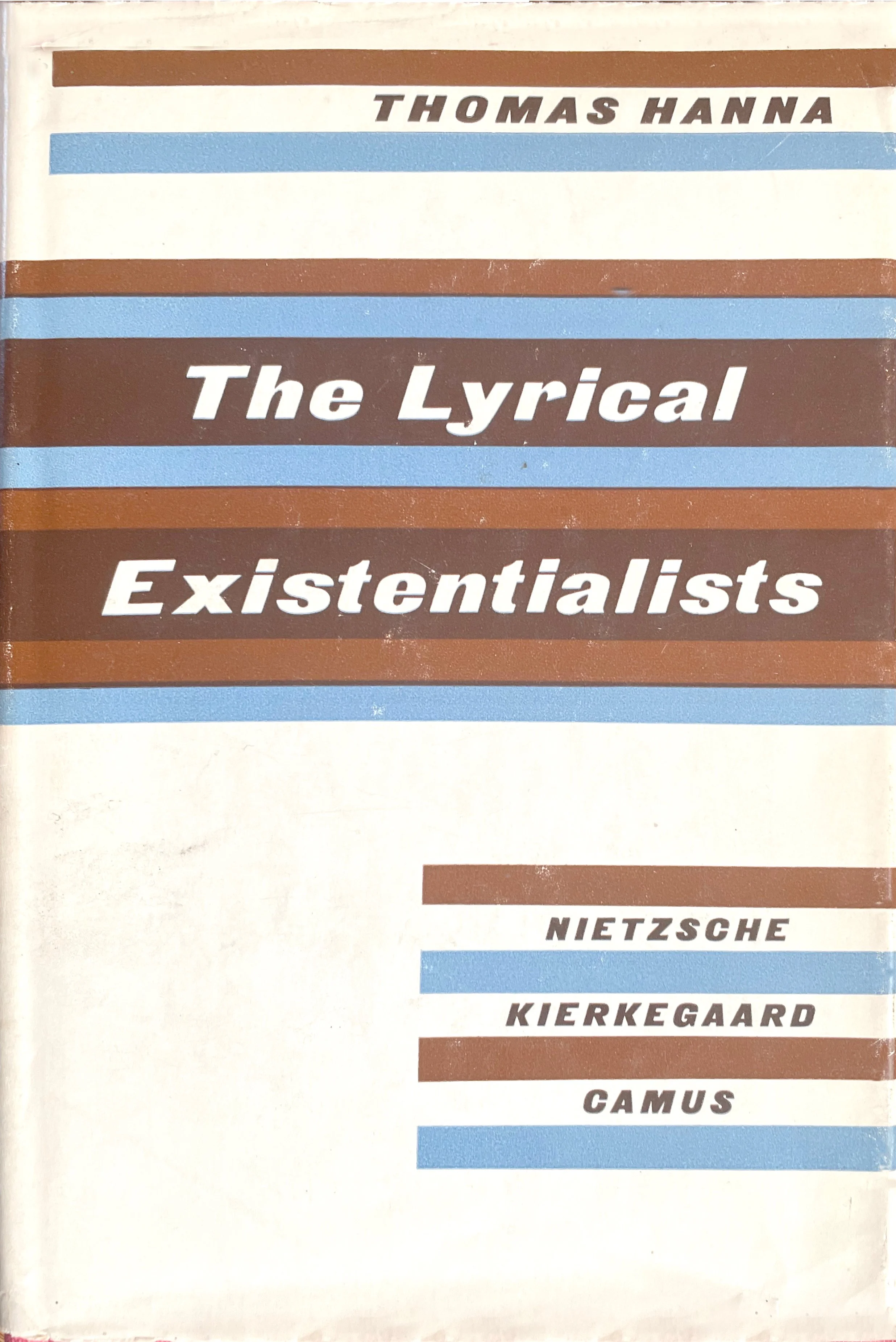

Upon completing college, Tom received a scholarship to attend the Ph.D. program at the divinity school of the University of Chicago. However, by this time Tom had become a self-proclaimed atheist. Despite his reservations, Tom began his doctoral studies and did extremely well in his classes. Tom decided to write his dissertation about existentialism, which did not go over well with his committee. It was only when the manuscript had been accepted to be published as a book that the divinity school's dissertation committee allowed him to write about philosophy instead of theology. After graduation, the manuscript was published with very little revision as The Lyrical Existentialists (Hanna, 1962).

Tom made it a point to enjoy life to the fullest. Tom savored great writing, the arts, travel, culture, and being with family as great events. Each experience Tom had was truly appreciated in the moment and then later contemplated in private. It was the intensity of his reflections that I believe affected his brilliant philosophical nature and eventually spawned the theory of Somatics.

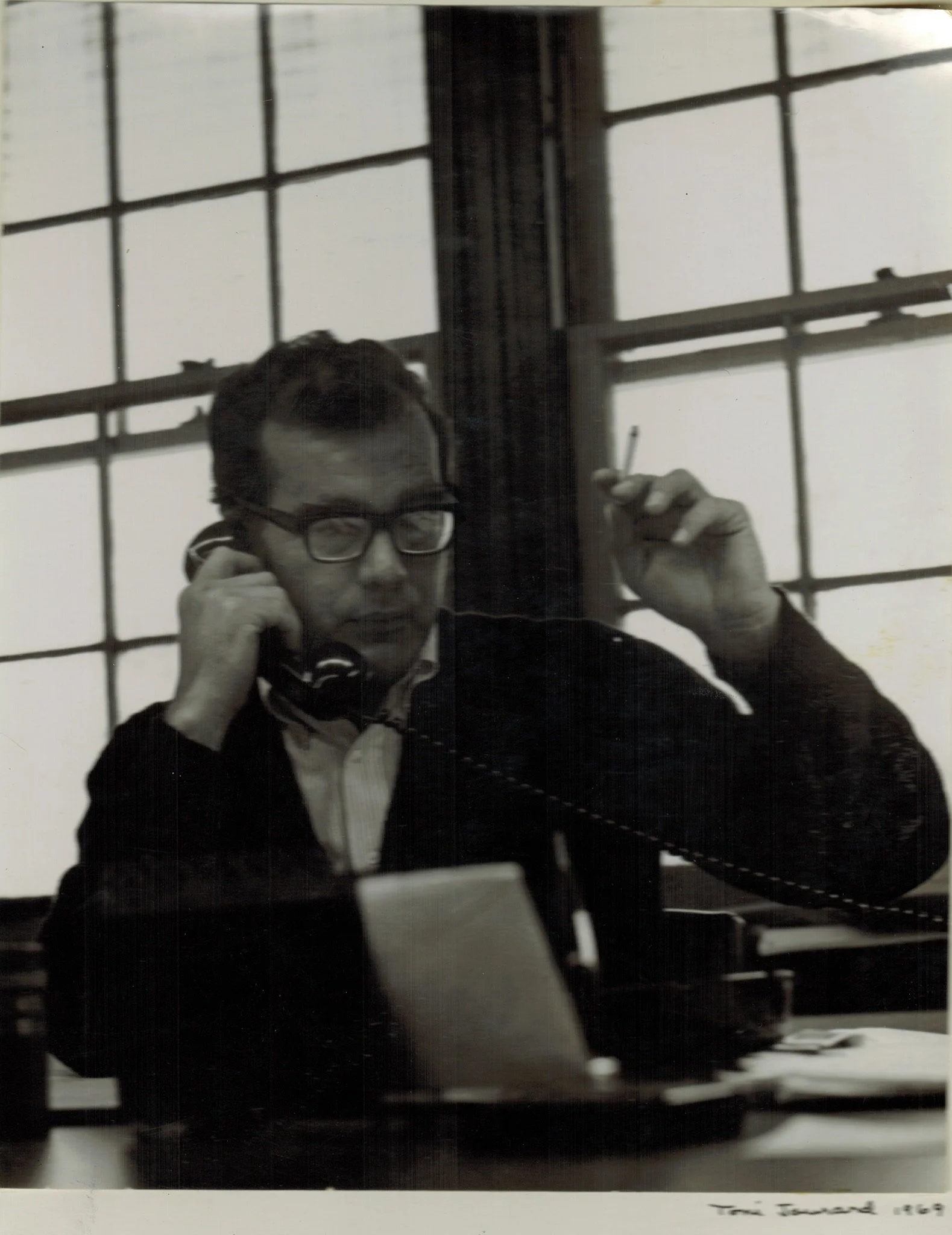

Thomas Hanna the existential, philosopher, professor.

For the rest of his life Tom proclaimed he was an atheist, but I have always felt that Tom was quite spiritual. His deep, introspective nature and reverence for all things authentic and beautiful saturated his being. Despite our family being supposed atheists, every Christmas Eve Tom would read the Christmas story from the Bible.

Tom loved good writing and I remember being transfixed by his voice; for instance, when I was in kindergarten, he read me Huckleberry Finn every night as a bedtime story.

Family music hour Roanoke Virgina early 1960’s

Tom Hanna had utter reverence for the beauty of the word and he was also a musician, singer and song writer. Making music together was a required family affair.

Tom the Philosopher

Tom writing in his studio in Novato, California using his beloved manual typewriter early 1980’s

As a young child I admired my father greatly, but I had no idea what he did for a living. I remember in kindergarten being asked what my father did for work and saying that I did not know. I later asked Tom, "Daddy, what is it that you do?" Tom told me, "I am a philosopher, Pumpkin." Struggling to understand, I asked, "What is a fishofer?" He replied, "If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound?" I left our little talk more than perplexed and the next day at school I told the class with conviction that "my daddy is a fireman!" Regardless of what Tom did for a living, I loved my father because he was bigger than life to me in extraordinary ways I never really understood. I now see that what I admired about him as a person was inextricably linked to his work as a philosopher. Tom's passion for existentialism was reflected in the way he lived life in the moment and the fact that he looked for meaning only from his direct experience. One reason Tom identified himself as an atheist might have been because he adamantly refused to look to non-worldly explanations to give him the answers to life. And he despised the New Age consumerism that was spreading like wildfire at the time. In short, Tom created his own meaning.

The Hanna Family with first cousins in Gainesville in the mid-1960’s.

As a human being, my father was both elegantly brilliant and authentically practical. In Tom's soon-to-be-published Somatology: An Introduction to Somatic Philosophy and Psychology, he states, "Authentic philosophical knowledge is as personally practical as it is elegantly theoretical. That is the philosophical stance of Somatics." I believe that Tom Hanna lived the philosophical stance of somatics; as a parent he modeled this stance as a way of life. Each day was designed to be embraced sensuously, lucidly, ethically, and positively and for Tom it was completely obvious that embodying a positive existential view was the only way to live one's life.

Tom giving a philosophy lecture at the University of Florida in the mid 1960’s

I grew up in a Gainesville, Florida, a college town in the conservative South where Tom was a professor and chair of the Philosophy Department. During my early years, Tom modeled through his behavior little tolerance for the prejudice and racism in the South. At six years of age, I remember answering the phone one day. A man wanted to talk to my father and I replied, "My father is not here right now, can I please take a message?" "Yes," the man said, "You can tell that n****r-loving father of yours that there is not enough room in this town for the both of us." I was shocked at the language the man used as I had been taught that the "n" word was a very, very bad word. I found out later that Tom had been on a local TV show speaking out in support of abolishing an old Negro curfew law. I believe that my father felt compelled to speak out against this unethical law because he loved and supported people who were authentic and lived their lives fully. African-Americans in Florida deserved to be treated fairly by the Whites and Tom was never afraid of speaking out against ignorance and inequality on behalf of others.

Tom the Revolutionary

Thomas Hanna had a huge thirst for life and knowledge. I was born in 1960, and from a young age I remember my father's fascination and participation in the rising youth revolution of the time. Radical graduate students and professors often visited our home for dinners and parties. Tom read and listened to the leading thinkers of the time and was fascinated with the love/peace movement. He would talk about these new ideas at length at home with the family and even ask our opinions about such things. He wanted to understand firsthand what the youth of America was experiencing. I have memories of going to many "hippie" events and of observing Tom experimenting openly with marijuana and LSD.

Hanging out with friends and family traveling in Tom’s VW camper, “Max”.

But it was the year of 1968, in particular, that the philosophical idea of "revolution" began to make first-person sense for Tom. In the summer of 1968, he loaded the family up in our sporty red Corvair convertible and headed off to Mexico so that he could write a new book and have a vacation all wrapped into one. The idea of a plane flight to Mexico was inconceivable to my father-after all, it would be much more of a cultural and educational adventure driving from Florida to Guadalajara, Mexico! Being the youngest of my siblings, I remember being squashed in between my brother and sister in the back seat with my hair blowing in every direction.

Hanna Family in the Chevrolet Corvair in the 1960’s.

After many days on the road, we arrived in Guadalajara at a basic home that my father had rented for the summer. My father chose this house because of the rooftop apartment that allowed him to retreat away from family and write his book. And write he did. Tom would spend days on end up on the roof and the family would never see him; then all of the sudden he would bound down the stairs, looking like a caveman but happily exhausted from writing. The family would then get in the car and explore remote villages and exotic pyramids, eat local dishes, and then play guitars at home.

Summer in Guadalajara, Mexico where Tom wrote Bodies in Revolt, 1969

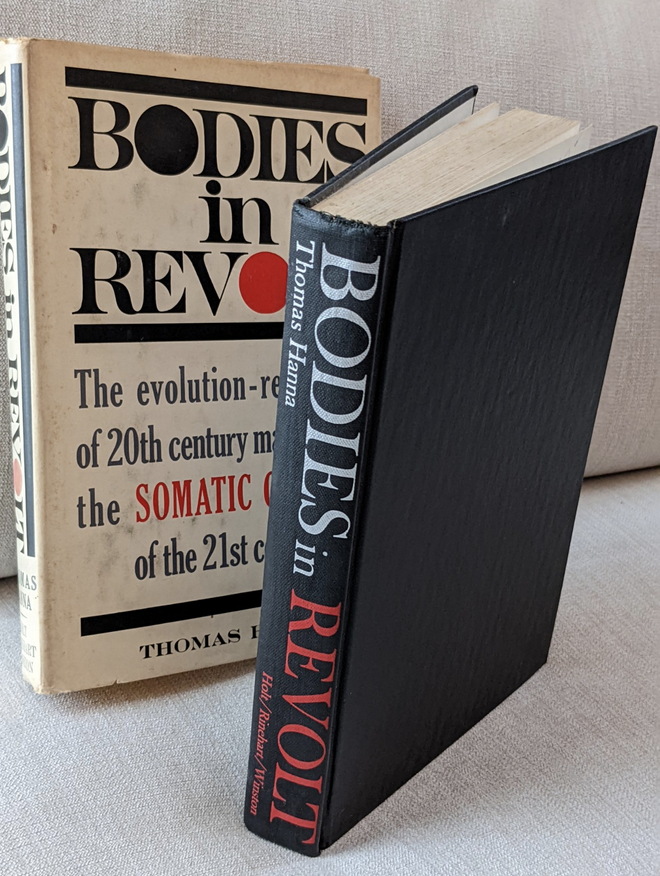

In the summer of 1969 my father wrote Bodies in Revolt: A Primer of Somatic Thinking (Hanna, 1970) in less than two months. Mexico continued to be a special place for Tom and he returned there quite often over the years to come.

Academic head shot of Thomas Hanna.

The seeds of Somatics were sown in that Mexican summer. Many of the ideas that Tom had put forward in that book were slowly penetrating and affecting his own personal life. For Tom, the meaning of academic life at the University of Florida was beginning to wither. Even though he had a prestigious position in a well-respected research university, Tom was incredibly frustrated with the small-minded academic bureaucracy.

I believe that a direct example of his mind set was the time he had a conversation with me when I was 10 years of age. Tom sat me down and said, "Honey, I want to tell you something- I don't want you to go to college. I'll tell you why- college is a place where people try to get you to think the way that they do- basically they teach you how NOT to think. If you really want to learn something, you find someone who knows that subject and learn directly from them or go to the libraries where the knowledge is contained beautifully in books and to boot, it's free!" At the time I had no idea why Tom was telling me this, but the truth is that during that time period Tom was incredibly frustrated with a particular situation within his department. As chair, he was responsible for both hiring and evaluating new professors. Tom had hired a brilliant philosophy professor with multiple degrees from Yale, a highly productive scholarly record, and an engaging teaching style. Tom greatly admired this professor and enthusiastically wrote him a glowing tenure and promotion review. Then the professor was denied tenure by the academic hierarchy and asked to leave the university, thereby ending his academic career. Tom was outraged because he knew that the only reason the professor was not retained was be cause his field of expertise was Marxist philosophy and this was during the Cold War era. Not only did the university career of Tom's colleague end, but Tom's belief in academia ended as well.

Subsequently, Tom became frustrated not only with his job, but also with the status quo of his personal life. My parents' marriage soon fell apart and my father went into a deep retreat. This was a transitional period for Tom, an inner revolution, which forced Tom to venture into new directions he had never before considered.

Tom was becoming fascinated with topics that were scientific in nature and began taking classes in physiology and neurology at the university's medical school. During this time, I remember that he took me to the university medical center to show me the human brains in large medical jars. He spoke with excitement and fascination as we touched the brains with our fingers and he told me how amazing the capabilities of the brain were, yet how little we really know about its functioning. I had no idea what to think of my father at that moment, other than that I knew he was going through a lot of changes. But to see him in the "mad scientist" phase was really strange. Tom was also becoming a bachelor again, a whole new person who was evolving.

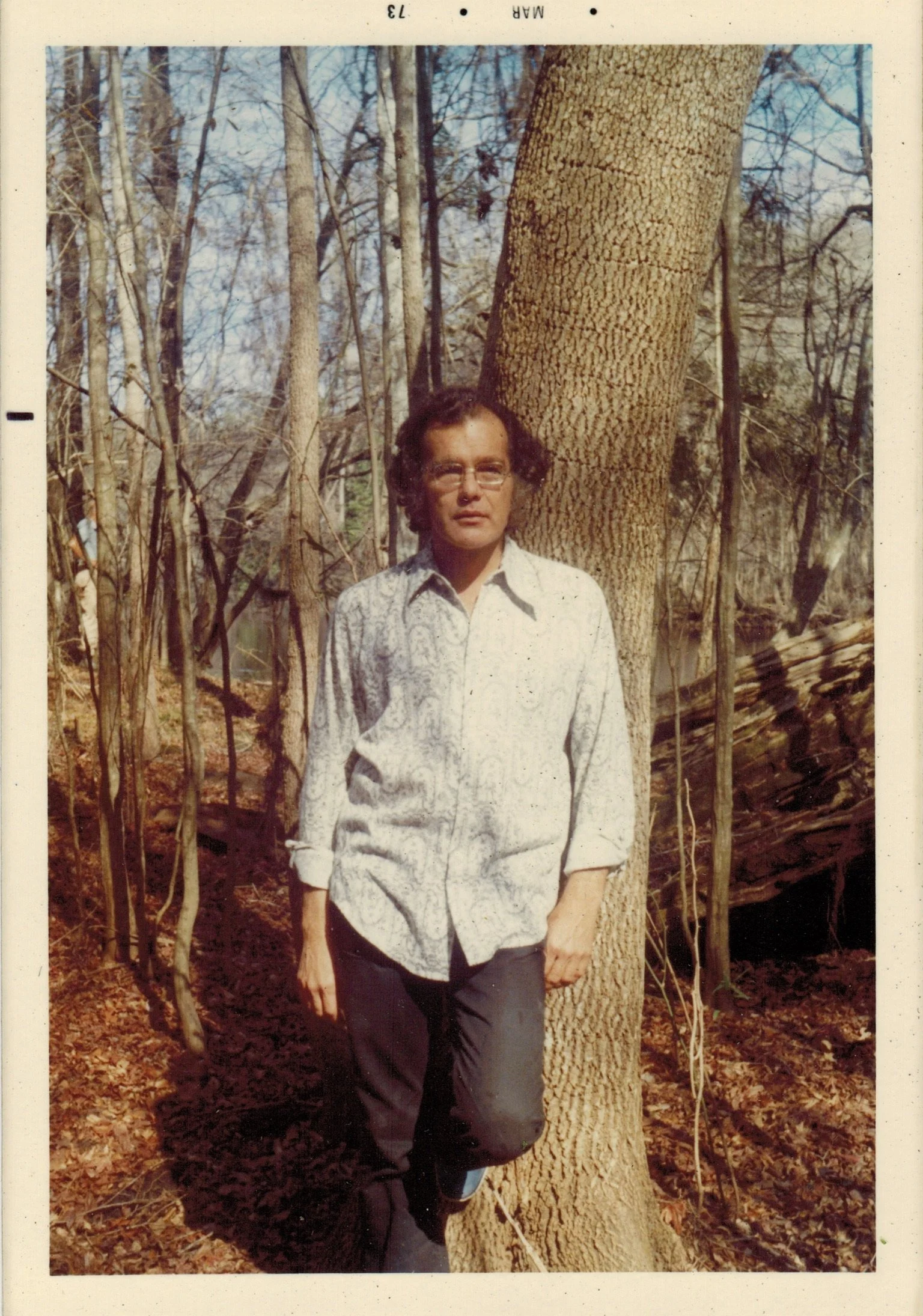

Tom, post divorce, 1973.

One of the most gloriously new things Tom learned as a single man was that not only could he cook by himself, but that he was quite a chef. Tom reveled in the fact that he could cook anything he wanted, anytime he wanted. I recall that visitations at Tom's new bachelor pad included having "Thanksgiving" dinner once a month. For my father, this transitional time seemed to be an opportunity for learning to live life in new ways and exploring possibilities.

Tom doing his favorite activity of swimming in the many crystal clear springs in Florida in the 1960’s

That my personal time with Tom was always an adventure is an understatement. I remember spelunking (cave camping) with graduate students for several days, tubing down rivers, weekend motorcycle rides down random country roads to see where they would lead us, and sneaking into cow fields to find hidden sinkholes with crystal-clear swimming springs. It was during this transitory time that Tom finally made the decision to quit his professorship at the university. By the end of this period, Tom's life had completely changed and he began to embrace his new role as a visionary.

The Hanna kids on weekend adventures with Tom.

Tom the Visionary

I recently re-read Bodies in Revolt: A Primer of Somatic Thinking (Hanna, 1970) and I was struck by Tom's uncanny ability to see in 1969 what would inevitably unfold over the next forty years. Many of the insights from this seminal book are quite clear as now we have firmly entered the information age and are in the midst of what Tom called the "revolution-evolution." Tom could see, even at that time, that we were moving from the industrial age to the technological, and that it was happening suddenly and swiftly. Tom felt this shift was a revolution because as biological beings we have not had time to humanly adapt to the sudden advances ushered in by the digital society. It is incredible to me that Tom wrote this book at a time when there were no personal computers, cell phones, internet access, or daily emails in our lives- yet Tom discussed in Bodies in Revolt that our new "mutant" culture will be seduced by, and fixated on, the pleasures of technological play, media entertainment, and instantaneous communication. Our fixations and dependence on information communication technologies (ICTs) have now become completely normalized into our daily lifestyles. In Bodies in Revolt, Tom points out that we play with our technological toys, but on a somatic level of experience we are not playful. We find ourselves thrust into this new technological age, and for a period of time we are "mutants." Tom saw this revolution as a positive time of adaptation illustrated through the works of Darwin, Freud , Lorenz, Reich, and Piaget, that human beings are adaptive by nature, and that we will eventually adjust to our new technological environment somatically. In Bodies in Revolt, Tom argues that when humans adapt to the new technological age somatically, we will no longer need to be dominated by "assimilative drives" that trap us into habitual and fixed patterns of behavior. At first, we will act as "mutants," learning to somatically adapt to the new era. Such somatic adaptation will be a positive evolutionary step for humanity! Rather than adapting to old industrial age schemas, we can instead use "sensual accommodative perception" or a somatic way of knowing and feeling- a form of co-evolution of soma and environment. The more expansive and inclusive our experiences are, Tom asserted, the better our ability not only to adapt, but to change. Our new perceptions will directly affect our resultant behavior.

Tom the Somatic Pioneer

Tom's perceptions had changed through his visionary thinking and so had his life. After my parents divorced Tom found himself without a career, a family, or a home to call his own. It was clearly a time for a new beginning and Tom moved to California to be with his newfound love, Eleanor Criswell, who was an Assistant Professor of Psychology in Sonoma State University's pioneering humanistic psychology program. Eleanor supported Tom both emotionally and financially as he struggled to find a new identity.

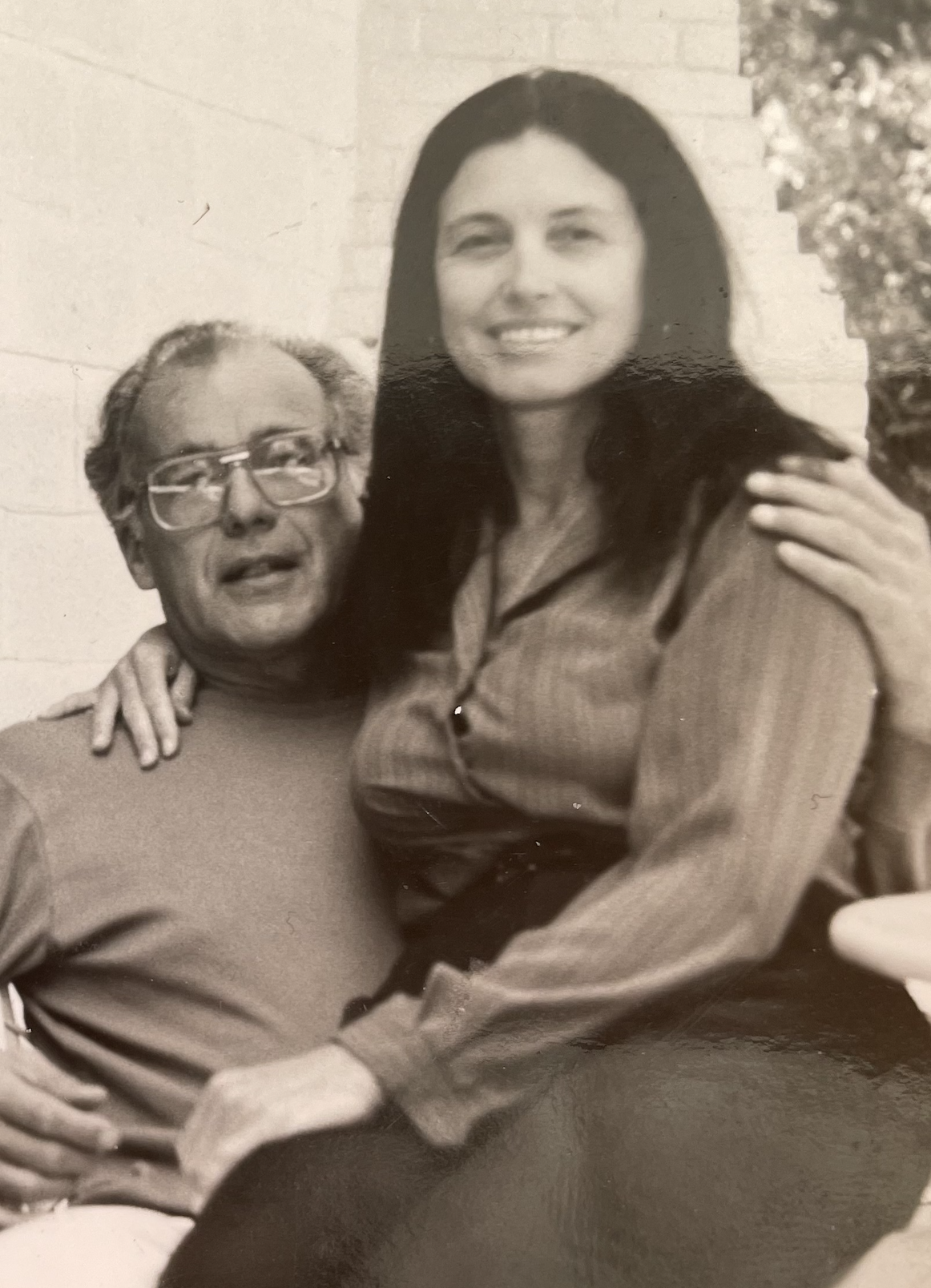

Eleanor Criswell and Thomas Hanna in the mid-1970’s

Tom began refining his ideas on the field of Somatics and consequently "discovered" Moshe Feldenkrais. I remember talking on the phone with Tom after he first met Moshe and hearing him use words like "extraordinary,""miraculous,"and "fantastic" to describe his experiences-and this was quite surprising because Tom rarely raved about any one. Fortunately, I experienced the excitement first-hand when I visited Tom and Eleanor in California, where I was able to observe the Feldenkrais training sessions at Lone Mountain College. I was 15 years old at the time. I was also able to observe Moshe and my father in more casual settings at Tom and Eleanor's home and I could see the reverence that Tom felt for Moshe Feldenkrais. It was indeed a catalytic encounter that helped crystallize for Tom the theory and the practice of Somatics.

Tom with Moshe and fellow participants at the first American Feldenkrais training in San Francisco 1975

In 1975, Tom and Eleanor founded the Novato Institute for Somatic Research and Training, where he practiced Somatics with thousands of clients over the next 15 years.

Tom and Eleanor in their Novato, CA home.

After the Feldenkrais trainings were over, I observed the visceral aspect of Somatics begin to permeate Tom's consciousness. Tom would often point out how he noticed the rolling hills resembling the sensuous curves of a human body, how a particular person's spine or retracted hip was affecting that person's gait, and in particular, Tom would notice how incredibly beautiful nature was all around him and so perfect in its effortless symmetry, vibrancy, and individuality.

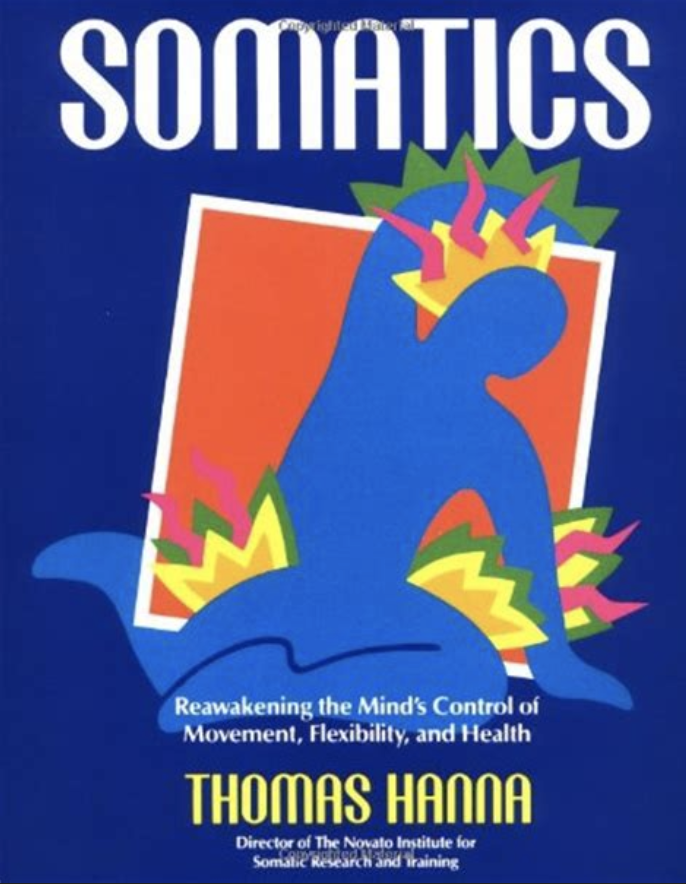

These new sensibilities alongside his hands-on work with clients, I believe, helped Tom to meld the Feldenkrais work with his own philosophy, and this new thinking was subsequently documented in the book Somatics (Hanna, 1988). Somatics explained the actual technique as well as the theory of why the Somatics exercises work. The book and succeeding materials have helped countless people recover from needless pain. But this book was only the beginning of what Tom imagined as the implications of Somatics.

Tom was a visionary thinker and knew that the idea of Somatics could be applied in any field, including psychology, and that this new perspective might possibly forever change the science of human experience. "My project in composing a somatic psychology is to identify in an experiential form those conscious experiences that are typical inhibitory areas exactly parallel to what I have discovered as typical 'bodily' inhibitions created by trauma and stress" (Hanna, 2007-08, p. 5).

Somatics training in Australia (early 1980’s)

Before his death, Tom was envisioning the field of Somatology as completely changing the way we think of ourselves and our relationship to the universe around us. It is sad that Tom was not able to finish his work or to fully develop his ideas.

For me, it was particularly tragic that when Tom died I was seven months pregnant with his first grandchild, a child whom he would never meet. I can only imagine the delight Tom would have had observing my son grow to adulthood. But Tom was a wonderful father and had a huge part in helping me grow to adulthood. Tom took pride in nurturing me to be a special person, someone whom he was very proud of in many ways. Throughout our parent/ child relationship, I always felt appreciated and adored by Tom and remember so well the way that Tom loved to laugh and use words in his own special way. For instance, he would often say in a wry voice, "My daughter plays the bass-oon" which always sounded humorous to me as he emphasized the "BASS" (said as in the large-mouth fish) first, then the "oon." The way he said it always made me laugh as I saw an image of myself playing a fish on a lampoon. But Tom always supported me, in being an orchestral bassoonist, or whatever else I did, because he loved me for who I was.

Tom and Wendell in the early 1970’s

Tom and I talked the day before his fatal car accident in 1990 and he shared with me many of his hopes and concerns for Somatics. He shared that he hoped that by having more practitioners doing the Somatics work, he would be freed to do more writing and lecturing. He told me that he had so much more to say through writing, lecturing, and philosophizing. He told me that he had come to terms with the fact that he was a philosopher at heart, not a practitioner. He was quite pleased that the summer trainings would allow Somatics to spread, and that the field would develop in more expansive ways.

Tom in Yosemite proudly posing.

Tom confessed that the teaching duties during the Somatics training were more intense than he expected and it was a real challenge for him to convey the work. Tom admitted that he never realized how difficult hands-on teaching could be, and he told me how much he appreciated the fact that I was a music teacher.

During that conversation, Tom also emphasized that he strongly felt that each person trained in Somatics should use it in his or her own unique way. His hope was that Somatics would flower into an array of exceptional diverse practices. I know Tom would be extremely happy with the work that Eleanor and all of the Somatics practitioners have accomplished since his death. As Tom said in the preface to the 1985 Freeperson Press edition of Bodies in Revolt, "The general acceptance and usage of the term Somatic in so many fields today betokens a new manner of thinking of ourselves in the breadth of our biological history and in the depth of our physiological reality."

Just as Tom wished for, today in the new millennium Somatics is still growing as a well-accepted and established area in many different disciplines and Tom would have taken huge delight in this fact.

I idolized Thomas Hanna, not just because of his accomplishments or his brilliance, but because as my father, Tom modeled for me a somatic way of being. I loved Tom because he showed me that life is about movement, music, flavors, colors, sensations, thoughts, feelings, and passion. Tom taught me that the glass is never empty, the world is always full of surprises and when the tree falls in the forest it does make a sound-you only have to listen.

Thank you, Tom.

Tom went to Scotland and reunited with the Hanna clan and here he proudly wears the Hanna tartan kilt in the Santa Rosa Scottish Games in the mid- 1980’s

References

Hanna, T. (1962). The lyrical existentialists. New York: Atheneum Press.

Hanna, T. (1970). Bodies in revolt: A primer in somatic thinking. Novato, CA: Freeperson Press.

Hanna, T. (1988). Somatics. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley.

Hanna, T. (2007). Somatology: An introduction to somatic philosophy and psychology (Part I). Somatics, 15(2), 4-10.

Hanna, T. (2007-08). Somatology: An introduction to somatic philosophy and psychology (Part II). Somatics, 15(3), 4-9.