In 1969, the same year humans first walked on the moon, Thomas Hanna wrote the book, Bodies in Revolt: A Primer in Somatic Thinking. In this seminal book he explained that the "evolution-revolution" we are now living in represents a critical turning point in human development where evolutionary change and revolutionary transformation converge. Now with the rapid development of AI capabilities, his concept of the evolution -revolution is more important than ever before. As AI rapidly outpaces human development, we're facing an evolutionary mismatch that demands a radical rethinking of what it means to be human in a technological age.

The Evolutionary Factor: Hanna believed we're witnessing actual evolutionary changes in younger generations who he called "proto-mutants" - the first adapters to live completely immersed in advanced technology. Just as humans evolved to lose traits they no longer needed (like strong little toes for tree climbing), Hanna argued that our reliance on basic logical reasoning might diminish as machines take over intellectual tasks.

The Revolutionary Factor: This involves a fundamental shift in how humans relate to themselves, others, and the environment. Rather than the traditional Western approach of environmental domination through "fear-aggression" and "constrictive conscious control," Hanna envisioned a move toward what he called "sensual accommodation" - a parasympathetic, receptive way of being that allows for symbiotic relationships. The concept essentially describes humanity's potential evolution from a species that survives through domination to one that thrives through conscious, somatic integration with its environment.

AI and the Somatic Evolution Revolution

We are living through what may be the most dramatic evolutionary mismatch in human history. While AI systems improve exponentially—doubling in capability every few months—human biology remains stubbornly tied to the rhythms of geological time. Our nervous systems, fine-tuned over millennia for a world of immediate physical threats, are now trying to navigate an environment where algorithms make split-second decisions that affect millions of lives, where information travels faster than we can process it, and where the very nature of work, relationships, and meaning is being redefined by machines.

The result is a human species caught between worlds: too advanced for our ancient programming, not yet adapted to our technological reality. This paradox isn't personal failure; it's evolutionary lag. We're running Stone Age software on a Space Age operating system, and the cognitive dissonance is tearing us apart.

The Nervous System Wars

Consider the daily experience of a typical American teenager. She wakes to notifications from a dozen apps, each engineered by teams of neuroscientists and behavioral economists to capture her attention. Her brain, evolved to scan for saber-toothed tigers, instead finds itself parsing the social dynamics of Instagram, the political outrage of Twitter, and the endless scroll of TikTok. This teenager possesses computational power in her pocket that exceeds what is needed to determine the complete sequence of the human genome, yet she reports feeling more anxious, purposeless, and disconnected than teenagers in any previous generation. She is simultaneously the most connected and most isolated human who has ever lived. She is what Hanna referred to as a “proto-mutant”, meaning she is one of the first (proto), adaptors (mutants) to have to deal with this situation for their entire lives.

The Technological Trap

In our current moment, we are in a world where algorithmic logic increasingly determines human possibilities—from what information we see, to whom we date, to what jobs are available to us. In his series, Beyond Bodies in Revolt, Hanna explains how the current technological trap began a long time ago with the advent of language. "When language was born, technology was born; humans had in that act thrown out the first lasso onto the environment and drawn the loop tight.” Hanna goes on to say, “We had captured a world—that world which we would bend to our needs and our adaptive imperatives." AI today represents, perhaps, the ultimate expression of this ancient human impulse to capture and control the world. But the question remains: who is capturing whom?

The teenager scrolling through her phone believes she is consuming content, but sophisticated AI systems are simultaneously consuming data about her preferences, behaviors, and psychological patterns. She is both user and used, consumer and consumed, in a feedback loop that Hanna would have recognized as the logical extension of humanity's technological trajectory.

The Accommodation Alternative

But there's another possibility, one that requires us to think differently about evolution itself. Rather than waiting for our biology to catch up to our technology—a process that would take thousands of years—we might consciously bridge the gap through somatic awareness.

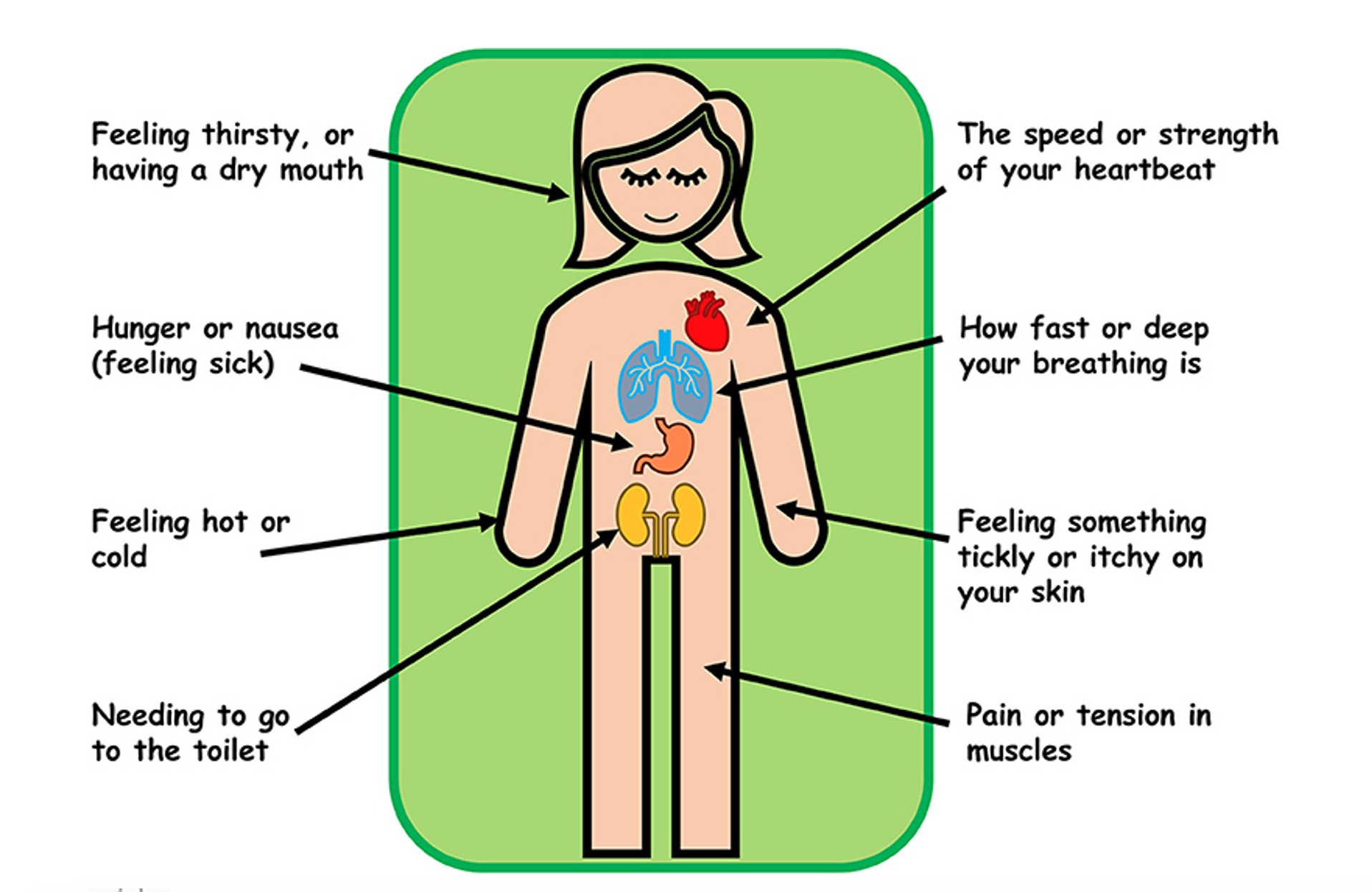

This is where the emerging field of Somatic Education becomes relevant. Somatics, the study of the body as experienced from within, offers something AI cannot: the ability to sense our internal state and adjust our responses in real time. While AI excels at processing external data, somatic awareness teaches us to process the data of our own embodied experience.

The distinction matters more than it might initially appear. When we operate from somatic awareness, we make fundamentally different choices about how to design and deploy technology. Instead of asking "How can we make this system more efficient?" we might ask "How can we make this system more conducive to human flourishing?"

Hanna argued that awareness of our internal state is inseparable from our relationship with the external world. When we learn to sense ourselves from the inside out, we naturally become more attuned to others and our environment. This internal awareness doesn't make us passive; it makes us responsive rather than reactive.

In the context of AI, this difference is crucial. Reactive humans create AI systems that amplify fear, division, and control. Responsive humans create AI systems that enhance collaboration, creativity, and collective intelligence.

The Assimilation Trap

The stakes of this choice are higher than we typically acknowledge. AI is not neutral; it amplifies the intentions and biases of its creators. When developed by humans operating from fear-based patterns—scarcity thinking, zero-sum competition, us-versus-them mentality—AI becomes a tool of what we might call "technological assimilation." It forces conformity, eliminates difference, and concentrates power in the hands of those who control the algorithms.

We see this pattern everywhere: facial recognition systems that work poorly on dark-skinned faces, hiring algorithms that discriminate against women, social media platforms that polarize rather than connect, and surveillance systems that turn citizens into suspects. As Hanna observed, “the marriage between efficient technology and efficient killing has historically gone hand and glove”. This is a pattern that continues in our surveillance capitalism era, where the violence may be psychological rather than physical, but the systematic dehumanization remains.

But when AI is developed by humans who have cultivated embodied awareness—the ability to sense their internal state and respond from a place of integration rather than fragmentation—something different becomes possible. Instead of technological assimilation, we get technological accommodation: systems that create space for difference, enhance rather than replace human capabilities, and distribute rather than concentrate power.

The Post-Scarcity Paradox

In Beyond Bodies in Revolt, Hanna states, “The two most crucial social events happening at the present time on this planet are, (1), Phase One, the technological revolutions of the underdeveloped societies, and (2) Phase Two, the cultural evolution-revolutions which arise in these societies once they have become technologized.”

Hanna's most prescient insight may be his observation about what happens after the Phase One technological abundance becomes widespread: "When the affluence of a technologized environment comes within the reach of all humans in a society, then the enormous adaptation of Phase Two inevitably takes place: for men must then live with that which they have created. And the crucial thing they must live with is the disappearance of the ancient fear of not enough that has been the trigger of human assimilative culture—as well as of human revolutions—for three million years."

We are living through this Phase Two adaptation right now. For the first time in human history, our primary challenges are not about scarcity but about abundance—too much information, too many choices, too much stimulation. The "ancient fear of not enough" that drove human development for millennia is being replaced by a new anxiety: the fear of being overwhelmed by too much.

This shift requires a fundamental reorientation of human consciousness. The survival strategies that served us for millions of years—constant vigilance, competitive acquisition, hoarding of resources—are not only obsolete but actively harmful in this current age of enormous technological advances. Yet our nervous systems haven't been able to keep up with this new scenario of rapid change and technological abundance.

The Generation Gap

Nowhere is this evolutionary mismatch more apparent than in the experience of young people who have grown up alongside AI. They are the first generation to experience what researchers call "ambient artificial intelligence"—AI that is woven so seamlessly into daily life that it becomes invisible. These young people often report a peculiar form of existential confusion. They have access to more information, entertainment, and social connection than any generation in history, yet they struggle with unprecedented levels of anxiety, and depression.

The problem isn't technology itself but the lack of proprioception— the sense of one’s own body in space and interoception—the ability to sense internal bodily signals. When we're constantly focused on external screens and stimuli, we lose touch with our own internal navigation system. We can communicate instantly with anyone on the planet but struggle to sense our own feelings or needs. This suggests a path forward that doesn't require choosing between human and artificial intelligence but rather learning to integrate them consciously.

The Somatic Integration

The future of human-AI collaboration may depend less on making AI more human-like and more on humans developing capacities that complement rather than compete with artificial intelligence.

AI excels at pattern recognition, data processing, and optimization within defined parameters. Humans excel at something entirely different: the ability to sense meaning, to navigate ambiguity, to create something from nothing, and to respond to the unexpected with creativity rather than programming.

But these uniquely human capacities require cultivation. They don't develop automatically; they emerge from practices that integrate mind and body, self and other, individual and collective awareness.

This kind of embodied somatic intelligence becomes crucial as AI takes over more routine cognitive tasks. The question isn't whether humans can out-compute machines—we can't. The question is whether we can develop forms of intelligence that are genuinely complementary to artificial intelligence.

A Tipping Point

We stand at a historical inflection point that demands conscious evolution. The power we now wield through AI requires a level of wisdom and responsibility that we can only develop by cultivating our full human capacities—not just our cognitive abilities, but our somatic, emotional, and relational intelligence as well.

This isn't about returning to some pre-technological past or rejecting the benefits of AI. It's about growing up as a species. It's about recognizing that the next stage of human evolution isn't about becoming more like machines but about becoming more fully human.

The choice we face is fundamental: We can continue to develop AI from a place of unconscious reactivity, extending old patterns of domination and control into new technological domains. Or we can learn to work with AI from a place of conscious responsiveness, using our technological capabilities to create conditions that support the flourishing of all life.

The workers displaced by automation, the citizens concerned about surveillance, the teenagers struggling with digital overwhelm—they are all experiencing symptoms of an evolutionary transition that we're only beginning to understand.

Hanna asks, “How do we transcend the problems of ecological and social anarchy in order to consolidate a humanistic, technological society?” The answer will determine not just the future of technology, but the future of what it means to be human in an age of artificial intelligence. Hanna states, “It is not "naïve" to be optimistic. It is not "unrealistic" to frame one's attitude to embrace that utopian society which is just as possible as the society of oppression. It is only humanly realistic to do so. No one knows all that it means to accept and know ourselves in our ancient somatic wholeness. No one has explored and made contact with all that is lying there, dormant and waiting through eons to be touched and brought to the light of everyday adaptation with this incredible world which flows about us”.

The path forward is neither a retreat from technological progress nor a surrender to algorithmic dominance, but a conscious evolution toward what we might call "somatic symbiosis" with artificial intelligence. As we stand at this unprecedented threshold, the teenagers scrolling through infinite feeds and the workers adapting to automated workplaces are not merely casualties of technological disruption—they are the pioneers of a new form of human consciousness. Their struggles with digital overwhelm and existential confusion are birth pangs of a species learning to integrate ancient wisdom with artificial intelligence, developing the embodied awareness necessary to create technology that serves life rather than diminishing it. The future belongs not to those who can compete with machines at their own game, but to those who can cultivate the uniquely human capacities—somatic intelligence, relational wisdom, creative responsiveness—that allow us to play and co-create alongside artificial intelligence rather than be consumed by it. In embracing our "ancient somatic wholeness" while consciously co-evolving with AI, we have the opportunity to fulfill Hanna's vision of a truly humanistic technological society—one where the marriage of human consciousness and artificial intelligence gives birth to possibilities we can barely imagine but must have the courage to explore and create.

References

Hanna, T. (1991). Beyond Bodies in Revolt, Part I. Somatics: Magazine-journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences, 8(2), 23-27.

Hanna, T. (1991). Beyond Bodies in Revolt, Part II. Somatics: Magazine-journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences, 8(3), 9-11.

Hanna, T. (1992). Beyond Bodies in Revolt, Part III. Somatics: Magazine-journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences, 8(4), 4-10.

Hanna, T. (1992). Beyond Bodies in Revolt, Part IV. Somatics: Magazine-journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences, 9(1), 4-12.

Hanna, T. (1993). Beyond Bodies in Revolt, Part V. Somatics: Magazine-journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences, 9(2), 4-9.