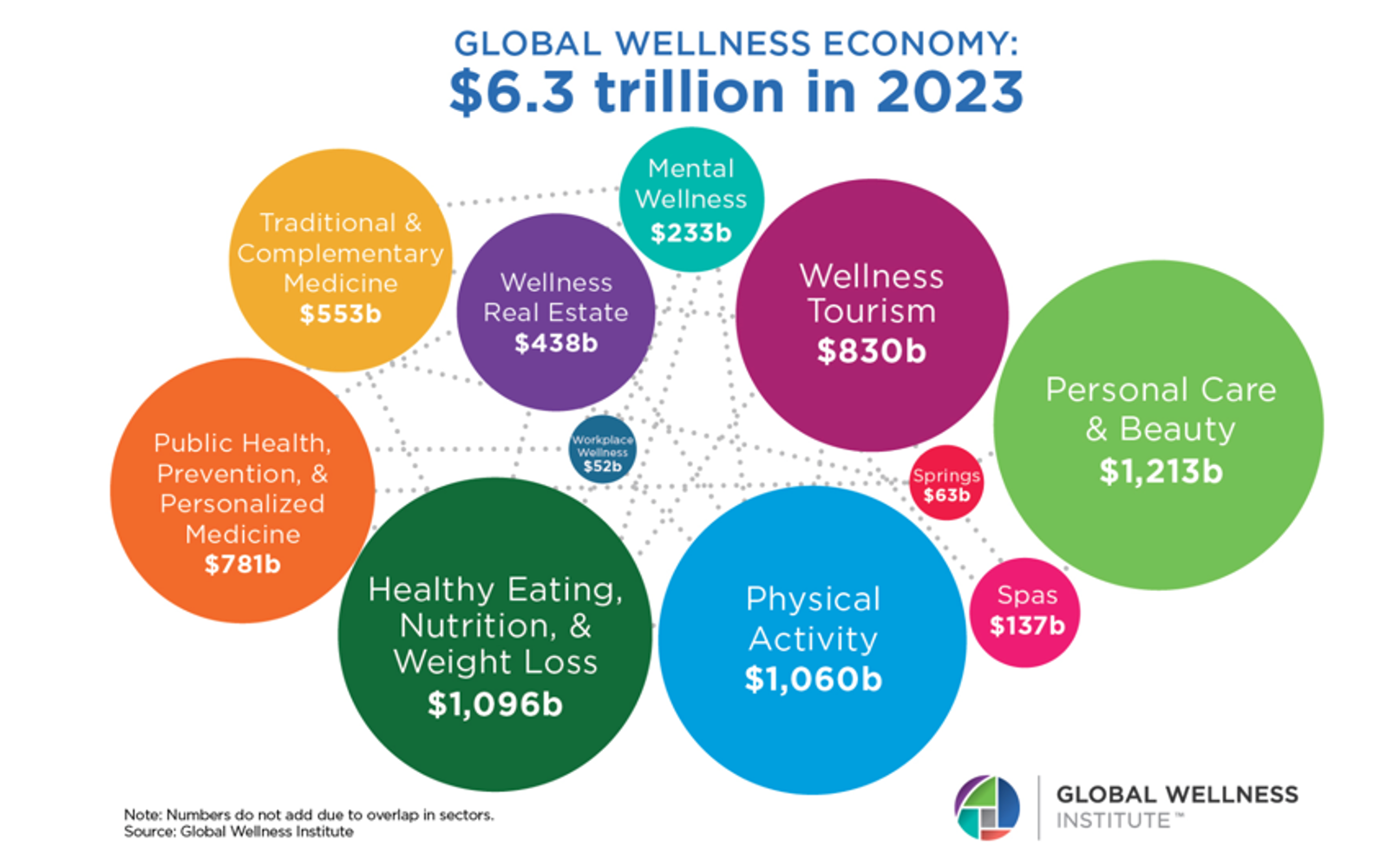

According to the Global Wellness Institute (GWI) the wellness industry is experiencing explosive growth, with its global economy reaching $6.3 trillion in 2023 and projected to hit nearly $9 trillion by 2028. Together, these interconnected sectors demonstrate how wellness has evolved from a niche market into a comprehensive ecosystem addressing physical health, mental wellbeing, beauty, travel, nutrition, and living environments. To understand this massive growth, it's essential to clarify how wellness differs from traditional healthcare.

Medicine vs. Wellness

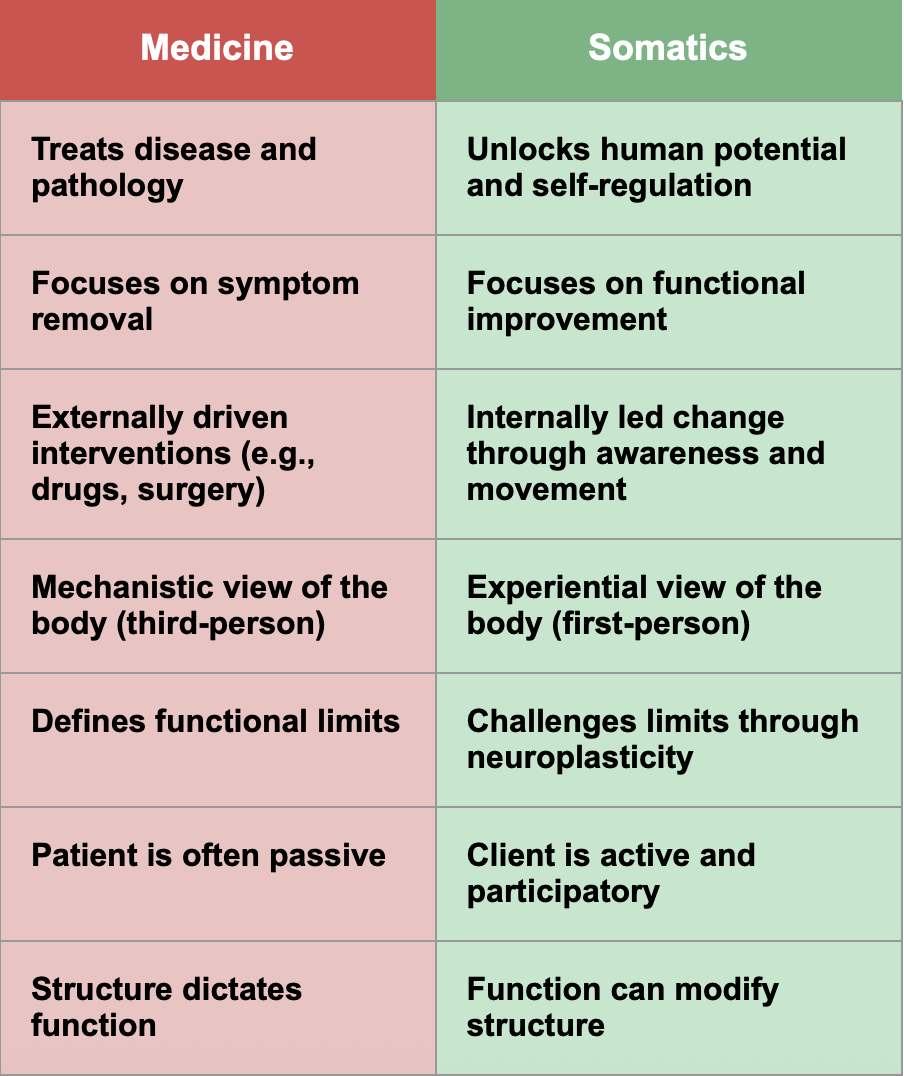

Medicine and wellness are distinct but complementary approaches to health. Medicine focuses on diagnosing and treating illness using clinical, evidence-based methods, while wellness emphasizes proactive, lifestyle-based strategies to prevent disease and promote well-being. Medicine is reactive and regulated; wellness is preventive and consumer-driven. Though their methods differ, both aim to improve quality of life, and they increasingly overlap in areas like chronic disease prevention, mental health, and integrative care. One field that exemplifies this integration of medical and wellness principles is Somatics, which emerged in the 1970s.

The Field of Somatics

Thomas Hanna coined the term "Somatics" when he introduced it in his article "The Field of Somatics," published in 1976 in the first issue of Somatics: Magazine-Journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences. At the time, there was no unifying term to describe practices that were educational, experiential, and embodied—distinct from both conventional medicine and traditional psychology.

In 1977, Hanna expanded on this framework in his article "The Somatic Healers and Somatic Educators," where he defined a somatic therapist as someone who understands the deep interconnection between body and mind. He wrote, "A somatic therapist sees that the fate of the human mind is utterly bound up with the fate of the body… the workings of the mind also have the power to transform the body." According to Hanna, somatic therapy could be divided into two complementary roles: the somatic healer, who focuses on curing ailments, and the somatic educator, who aims to enhance a person's capacity and awareness. Both share the common goal of improving human life, though their methods and intentions differ.

A comparison between traditional medicine and somatics highlights two fundamentally different paradigms for understanding and improving human health. Traditional medicine focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of disease, aiming to eliminate symptoms through external interventions such as pharmaceuticals, surgeries, or manual procedures. It often operates from a mechanistic, third-person perspective in which the body is viewed as an object to be fixed. Patients are typically passive recipients of care, and the emphasis is placed on structural correction—treating the body’s components like parts of a machine. Medicine tends to define the limits of human function based on clinical averages or pathological norms.

In contrast, somatics emphasizes the individual’s capacity for self-awareness, self-regulation, and internal transformation. Rather than treating disease, somatic practices aim to enhance total functioning by engaging the client in conscious, sensorimotor learning. Somatics views the body experientially—as both a structure and a lived, first-person experience. The somatic approach treats awareness as a real neurological function that can be trained to reshape how the body moves, feels, and behaves. Clients are active participants, not passive patients, and change emerges not through force but through subtle reorganization of function. Where medicine often addresses limitations, somatics works from the premise that human potential is open-ended—and that by refining function, we may transform structure in ways that are unpredictable, profound, and deeply personal.

While these principles define somatics broadly, somatic healers and educators apply them through contrasting therapeutic methods.

The Somatic Healers

Healers employ techniques such as trembling, stress positions, convulsions, and sobbing to induce catharsis—a release of repressed emotion through physical and emotional expression that offers therapeutic relief. This method is grounded in Reichian theory, which posits that emotional repression manifests as chronic muscle tension that blocks awareness and impedes the natural flow of energy. The focus is on healing through the removal of symptoms, with the assumption that muscular tension is pathological. By releasing this tension through physical catharsis, the body moves toward relaxation, which is seen as a return to health.

Key pioneers in the field of somatic healing were innovators who redefined therapy by making the body central to emotional and psychological transformation. From Wilhelm Reich’s idea of “muscle armor” to Peter Levine’s trauma-informed Somatic Experiencing, each practitioner offers a unique method rooted in the body’s intelligence. Each approach is considered somatic—not just treating the mind, but listening to and working through the body itself.

The Somatic Educators

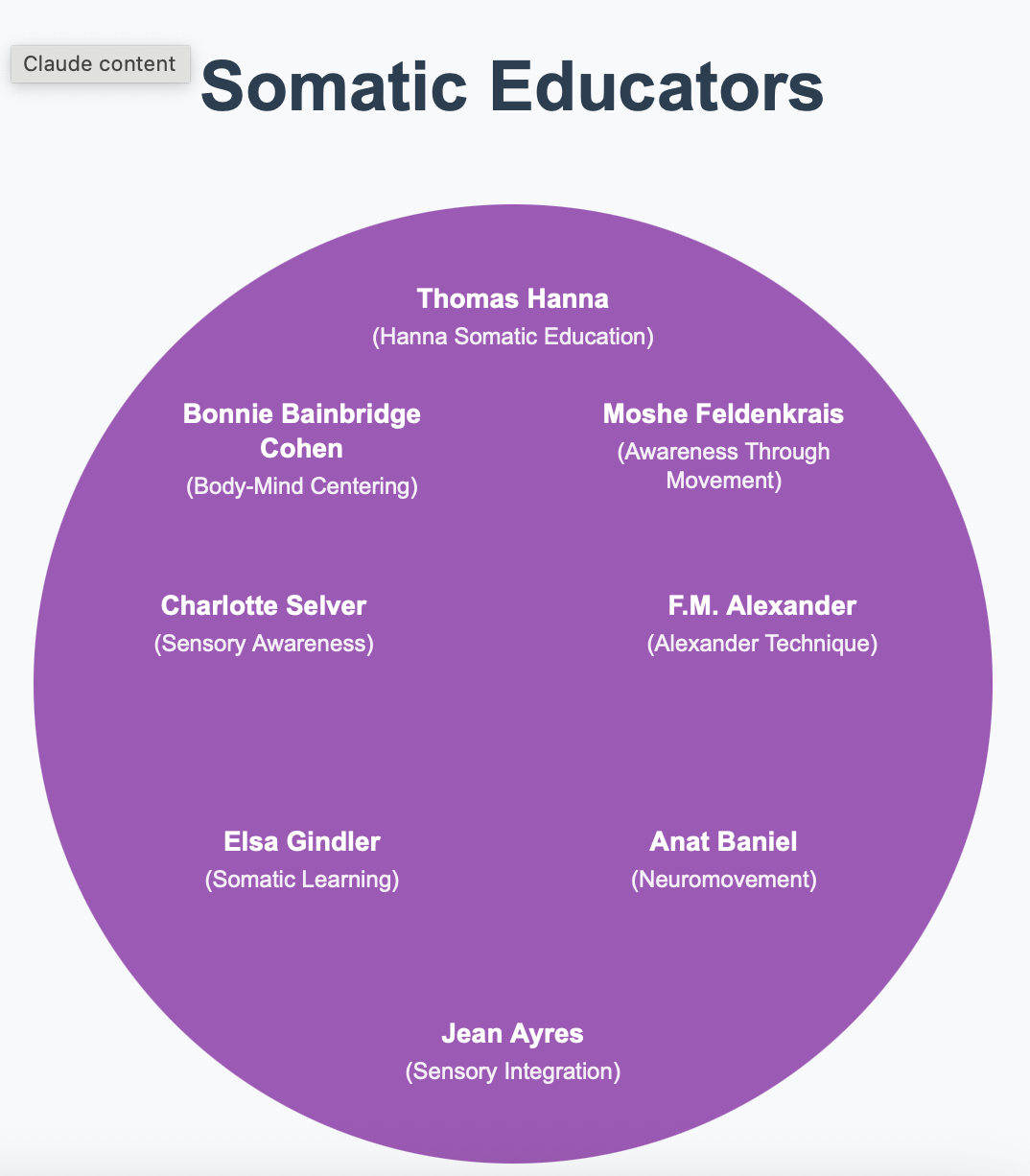

Somatic educators focus on learning rather than curing. Their primary goal is to cultivate awareness, coordination, and functional movement through gentle exercises, sensory training, and focused attention. They view humans as self-regulating, self-correcting, and capable of continual improvement.

Rather than aiming to eliminate pathology, somatic educators prioritize education over treatment. They encourage growth, enhance ability, and foster awareness. Their approach is grounded in the belief that function takes precedence over structure—improving movement and attention naturally leads to better posture, health, and structural alignment.

Educators use movement as a tool for neurological learning and transformation. Unlike healers, whose work may center on psychological models, somatic educators base their methods in neurophysiology. They see conscious awareness as a measurable neurological function that shapes how we move, feel, and grow. By enhancing this awareness, educators help re-pattern the nervous system, leading to lasting improvements in physical function and structure.

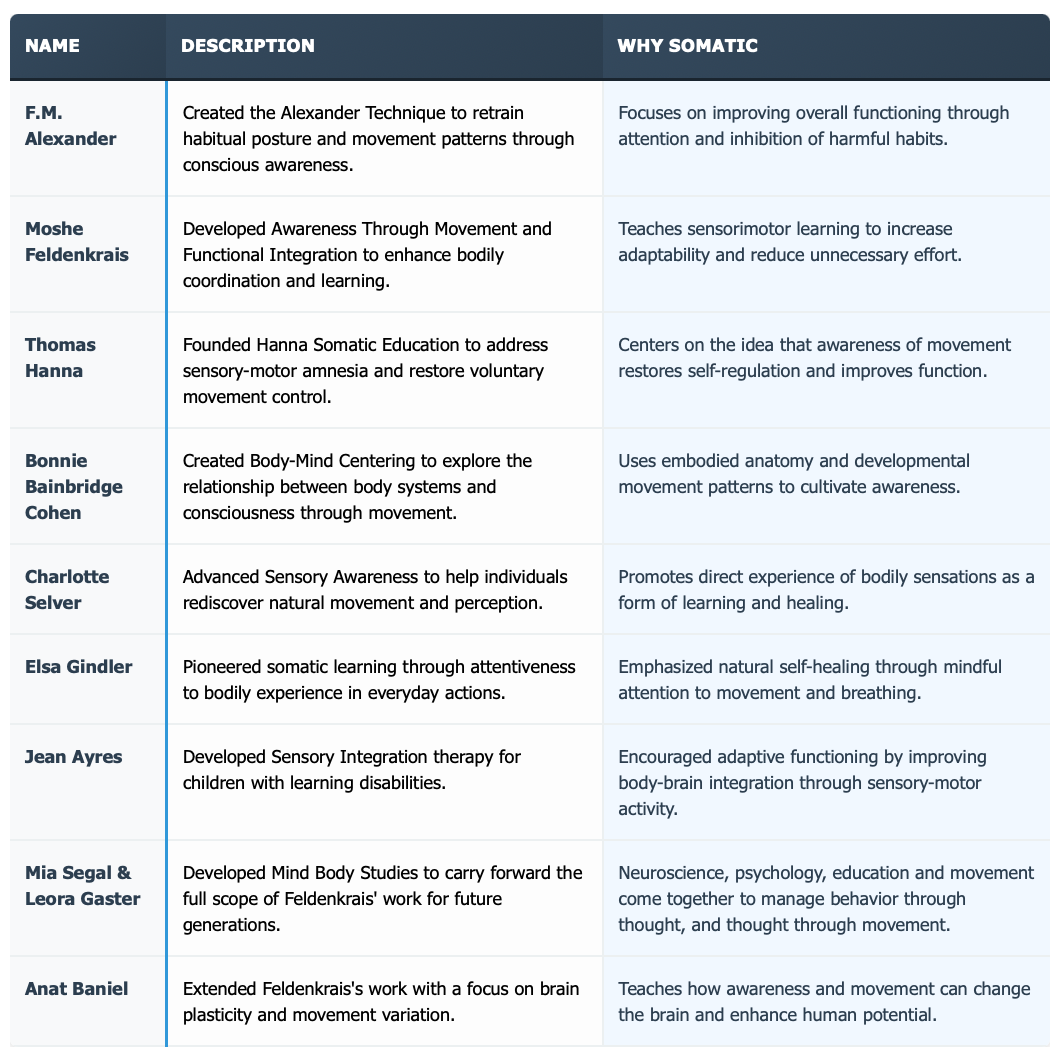

Key Somatic Educators

The table above highlights key pioneers in the field of somatic education, each associated with a unique approach to improving movement, awareness, and function. Together, these educators illustrate a common principle: somatic learning is rooted in conscious, internal experience rather than external correction.

Other Popular and Fringe Somatic Modalities

Today’s wellness industry showcases a remarkably wide range of healing modalities—so broad, in fact, that it can be overwhelming. Some of these approaches may seem fringe or even controversial. Yet many share a common foundation: the belief that trauma is stored in the body. In this sense, they may still be considered “somatic,” as practitioners aim to release trauma or energetic blockages through body-based methods. What unites these diverse practices is a core idea—that healing must involve the body, even if the individual plays a less active role in the process.

When Wellness Practices Are Not Somatic

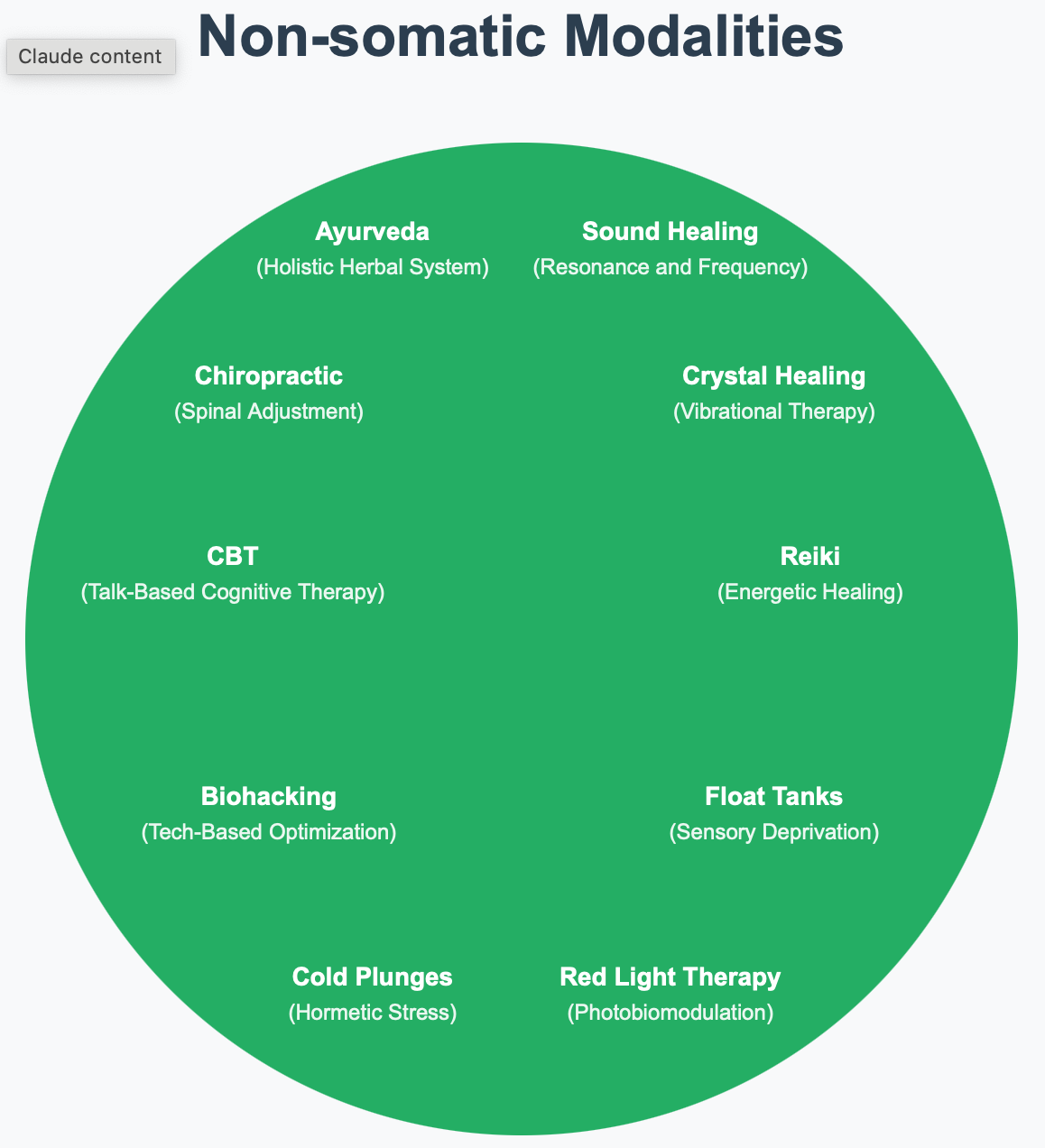

A wellness practice might be considered non-somatic when it lacks internal awareness or learning, emphasizes external outcomes over conscious bodily experience, or uses techniques that do not involve first-person, felt experience or attentional control. For example, traditional seated meditation may be non-somatic if it focuses solely on mental activity without incorporating body awareness. Similarly, Pilates or yoga practices that prioritize technique, form, or fitness goals over internal sensing fall outside the somatic realm. Massage therapy offered purely for relaxation—without engaging the client’s awareness—also qualifies, as do martial arts practiced primarily for competition or skill execution without attention to embodied experience. Dance or movement forms that center on choreography and performance, rather than inner sensation, are likewise non-somatic.

Many wellness practices, while potentially therapeutic, do not qualify as somatic because they lack active engagement with body awareness or sensorimotor learning. These practices—including Reiki, crystal healing, sound healing, Ayurveda, chiropractic, CBT, biohacking, cold plunges, red light therapy, and float tanks—share a common feature: the client remains largely passive or the intervention relies on external tools or biochemical processes. Unlike somatic practices, which prioritize conscious movement, attentional control, and embodied learning, these methods operate without cultivating first-person bodily awareness or self-regulation.

According to Thomas Hanna, the defining difference is that somatic practices cultivate conscious awareness and self-regulation, whereas non-somatic practices, even when involving the body, do not emphasize these internal processes.

The Future of Somatics in the Wellness Industry

The future of somatics will likely be shaped by professional organizations like the International Somatic Movement Education and Therapy Association (ISMETA), which establishes professional standards and guiding principles for the field. Founded in 1988 as a not-for-profit organization, ISMETA brings together individuals and organizations committed to advancing the profession of Somatic Movement Education and Therapy.

ISMETA organizes somatic practice around four core pillars: observation, anatomy, movement re-patterning, and guided communication. Within this framework, the organization supports a diverse range of specialized approaches, including ecosomatic nature practices, dance-oriented somatics, breath work and pain awareness, developmental movement for children and teens, creative arts integration, and evidence-based neuroscientific methods.

Variety of practices within ISMETA

This structure allows ISMETA to maintain professional consistency while embracing the rich variety of somatic practices that serve different populations and therapeutic goals.

Conclusion

As the wellness industry continues its rapid expansion, somatics stands out as a vital and transformative paradigm—one that centers on embodied learning, self-awareness, and the innate capacity for self-regulation. Unlike many wellness modalities that rely on external interventions, somatic practices empower individuals to participate actively in their own growth and healing through conscious, internal engagement. This perspective challenges the prevailing outcome-oriented model by emphasizing that lasting change emerges not from being fixed, but from learning to sense, feel, and reorganize from within. Thomas Hanna captured this idea when he wrote, “The limits of human potential for self-modification may be limitless.”

As consumers and practitioners navigate the vast landscape of wellness offerings, a clear understanding of what defines somatic practices—and how they differ from non-somatic approaches—can lead to more informed choices. In doing so, we open the door to deeper well-being, greater authenticity, and a fuller expression of what it means to be fully human.

References

Hanna, T. (1977). The Somatic Healers and Somatic Educators. Somatics: Magazine-Journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences, 1(3), 48-52.