The way we consume information today is very different from how our parents and grandparents did back in the day. Back then, people relied on trusted newspapers, journals, radio programs, and news anchors, like Walter Cronkite, whom most agreed were reliable sources.

Today, we increasingly depend on digital content curated by algorithms to guide us through social media and internet searches.

Unfortunately, these systems are designed to keep us engaged longer by serving content that aligns with our existing beliefs or triggers emotional reactions. As a result, they create “filter bubbles” and “echo chambers” that reinforce what we already think. Perspectives outside of these bubbles are filtered out. We simply don’t believe what others outside our informational ecosystem are saying. This fragmentation makes it difficult to engage in productive discourse on complex or divisive issues, because we’re no longer working from a shared set of facts or truths.

Thomas Hanna in the mid-1960’s

Decades ago, Thomas Hanna, the founder of the philosophy of Somatics, proposed that our bodies don’t just move through reality, they shape it. He called this process ontic projection: the idea that each of us constructs reality from within, based on our sensory and emotional experience. We might think of ontic projection as a kind of ‘inner lens’ or somatic aperture, that both perceives (receives) and projects (influences) its reality. We don’t just observe the world, we shape it through how our bodies feel and interpret what’s happening. In the age of filter bubbles and disinformation, Hanna’s theory may be more relevant than ever.

Ontic Perception

In Thomas Hanna's article "Ontic Perception: A Function of Human Survival”, he argues that perception is not an act of passive reception but an active process. Reality emerges from the inside out through the soma—our living, sensing body—which filters stimuli and projects a coherent world that feels real because it aligns with our inner physiological and neurological organization. This process enables us to distinguish between "me" and "not me," between "here" and "there." As Hanna explains, "out of a limitless ocean of possible realities, ontic projection gives us a single skein of reality that can be faced, handled, and lived with".

Hanna, T. (1981). Ontic Perception: A Function of Human Survival. Somatics: Magazine-Journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences, 3(2), 55-60.

Thomas Hanna was deeply fascinated by the question, “What is real?” He regarded it as one of life’s most important inquiries. He drew the concept of ontic projection from existential phenomenology, particularly from the work of Martin Heidegger. Heidegger used the term to describe how human beings (Dasein) project meaning onto the world, often unconsciously.

Hanna interpreted the question of “what is reality?” through a somatic lens. For him, as a soma—a self-regulating and integrated being— we require the external world to serve our survival needs. That survival depends on having a stable and shared sense of reality. Without this perception, we would struggle to recognize environmental threats and experience greater interpersonal conflicts with the people around us. A stable understanding of what exists "out there" allows us to move safely through life.

As Hanna explains, “The question of reality involves everything, the total physiological process as well as the total experiential process.” He emphasized that “in the human soma the ‘mind’ and ‘body’ coalesce within a single process,” and described reality as “a functional quality that we give to our experience of ourselves and our world.”

Ontic projection refers to how we understand “thereness” and “nowness” in our sensory experience. While the soma is often thought of as a body-centered experience, it also encompasses a vast range of mental activity. Hanna notes that “the first significant discovery about reality is that it is a human projection, it is something we do with stimuli, not what the stimuli do to us.” This selective process means that “we perceive only what we are prepared to perceive.” The result is what Hanna calls “the sense of reality,” which he defines as “an immediate knowing and sensing of what is the case and what is not, whether it be rational, balanced, proportional, ordered, or just the opposite of this.”

Filter Bubbles

Today, social media filter bubbles have clouded public perception and fueled misinformation and epistemic fragmentation in ways Thomas Hanna may never have imagined. For example, during the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election, social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Truth Social, and Facebook created starkly different information silos depending on one's political alignment.

On the right side of the political aisle, narratives focused on election fraud, suppression of conservative voices, and “deep state” interference. On the left, the dominant concerns were voter suppression and threats to democracy. Even when confronted with the same facts, such as vote counts or candidate statements, each side interpreted the information through the lens of its own filter bubble.

These algorithmically reinforced filter bubbles deepened polarization, eroded shared understanding, and made collective action increasingly difficult.

Echo Chambers

While filter bubbles are algorithmically generated, presenting you with content based on your past behavior, echo chambers arise from intentional social choices. You choose your peers, groups, or platforms (such as Podcasts, Reddit groups, Instagram, YouTube, Substack, or Discord) to reinforce your existing beliefs and norms. For instance, this was seen during the Israel–Hamas conflict, where pro-Israel and pro-Palestine communities shared highly curated media, often omitting context or circulating deepfakes. In the case of vaccine discourse, anti-vaccine communities formed private groups where rare side effects were exaggerated and government conspiracies promoted. In contrast, other communities embraced an uncritical belief in the absolute safety of vaccines, failing to acknowledge scientific complexity or evolving evidence.

Echo chambers can also be shaped by geography. Urban coastal cities and rural communities often function as large-scale cultural echo chambers. This divide is reflected in the language each side uses to dismiss the other with terms like “flyover country,” “uneducated,” or “backwards” being directed at rural areas, while phrases like “woke elites,” “coastal snobs,” and “fake news” used to disparage urban progressives.

Urban echo chambers tend to prioritize intellectual abstraction and scientific reasoning, whereas rural echo chambers often emphasize local trust, and visceral values.

The current phenomena of filter bubbles and echo chambers reflect Hanna’s ontic perception in that what we take as real is not determined by the information itself but by how we project meaning onto it.

Parallel Realities and Ontic Projection

Today, people often live in parallel informational realities such as climate denial versus climate science, or QAnon conspiracies versus fact-based reporting. Each reality feels “true” to its participants because it is internally consistent and somatically reinforced.

This occurs because ontic projection, our capacity to project meaning onto the world, is culturally shaped. It can be suppressed or enhanced depending on the environment. Competing realities are not necessarily irrational; they emerge from distinct forms of somatic-cultural training that determine what counts as real.

These strong senses of reality, however, are not innate, they are formed. We are not born with a fixed worldview. Children naturally engage in a more open and less fixed ontic projection through imaginative play and a powerful sense of wonder. As the brain matures, this capacity becomes increasingly inhibited.

Different cultures selectively train individuals to accept certain projections as real and dismiss others. For example, in many Western societies, hearing voices is typically labeled as a symptom of psychosis, while in some Indigenous or religious cultures, the same experience may be interpreted as a form of spiritual communication or shamanic calling. In one culture, emotional restraint may be seen as a sign of maturity and mental health, while in another, expressive emotional release may be viewed as healthy and necessary. As a result, even the idea of "sanity" becomes culturally relative and shaped by what a society deems acceptable perception and behavior.

What is the Arbiter of Truth?

How can we, as somas, decide what is true when the sensory information we gather has already been shaped, filtered, or manipulated for purposes that may have nothing to do with our own needs or desires?

In a world saturated with curated digital environments, emotionally charged content, and identity-driven narratives, we can only take this external information inward and integrate it into our somatic nervous systems. The disequilibrium we feel, the sense that something is off, can be deeply unnerving. This dissonance often manifests in various ways. We may experience anxiety and chronic stress when our internal sense of reality does not match the external world we are presented with. Cognitive fatigue can arise as we struggle to sort fact from fiction in a constant stream of conflicting information. Emotional dysregulation may be triggered by narratives designed to provoke outrage, fear, or tribal loyalty. We might also experience somatic symptoms such as tension, insomnia, digestive issues, or pain without clear physical cause, reflections of unresolved internal conflict. Over time, we may even feel a loss of agency, as we unconsciously internalize beliefs and behaviors that are externally imposed or reinforced through algorithms.

Consider the case of Lena, a massage therapist who began reading online articles about crystals and chakras as part of her interest in energy healing. Curious to learn more, she joined a few spiritual wellness groups on social media. Over time, her feed, shaped by algorithmic recommendations, began to shift. Alongside content on mindfulness and healing, she was increasingly exposed to anti-establishment health narratives, including vaccine skepticism and conspiracy theories about “big pharma.” Though she didn’t initially believe these claims, she noticed a growing unease in her body. She experienced tight shoulders, disrupted sleep, and a sense of vigilance whenever she encountered mainstream medical information. Her somatic experience had changed. What she once viewed neutrally now triggered anxiety. The filter bubble influenced not just her thoughts but also how her body responded to the world.

Somatic Practices for Regulating Ontic Perception

Without a stable somatic compass—the ability to sense and regulate from within—it becomes increasingly difficult to discern what is true. Our ability to navigate reality depends not only on what we perceive, but also on how we process, integrate, and embody those perceptions. In a fragmented world, cultivating a more reliable sense of truth requires turning inward and strengthening the body’s role as both interpreter and stabilizer of perception.

The following practices may help support a more grounded somatic and ontic awareness.

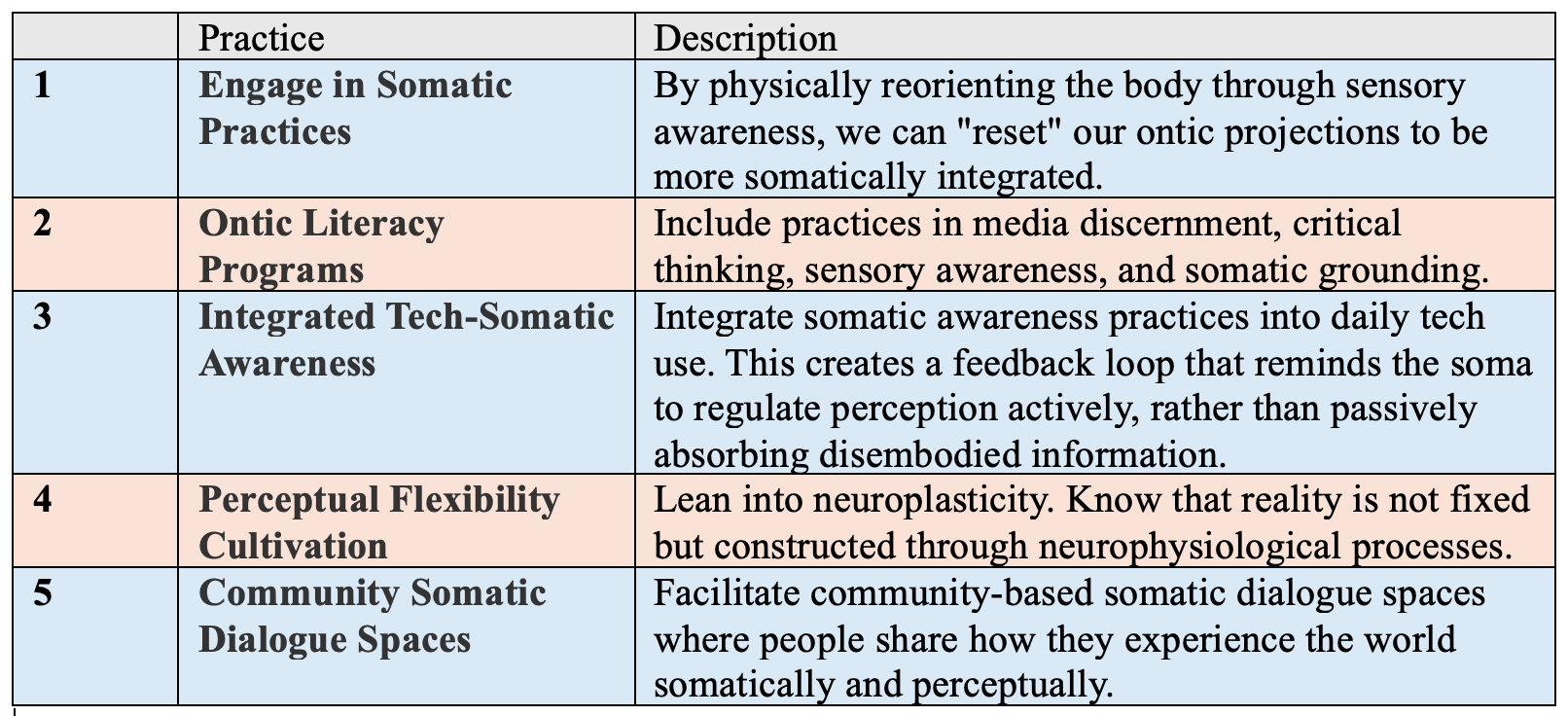

1- Incorporate practices like Hanna Somatic Education, or other body-based therapies, to reorganize one’s somatic experience of reality. By physically reorienting the body through sensory awareness, we can “reset” our ontic projections by aligning perception more closely with an embodied reality rather than externally imposed narratives. Somatic therapies can help individuals construct a new, functional sense of “what is,” not by forcing belief changes, but by altering the way the soma processes and organizes.

2- Develop ontic literacy programs such as courses or workshops that teach people how perception is constructed, filtered, and shaped by language, culture, identity, and somatic conditioning. This could include practices in media discernment, critical thinking, sensory awareness, and somatic grounding.

3- Integrate somatic awareness practices into daily tech use. For example, brief body scans or breath awareness exercises before and after engaging with social media, news, or high-stimulation environments. This creates a feedback loop that reminds the soma to regulate perception actively, rather than passively absorbing disembodied information.

4- Lean into perceptual plasticity. The understanding that reality is not fixed but constructed through neurophysiological processes. Encourage curiosity and play with alternative perspectives through movement or imaginative inquiry. By realizing that “reality” is shaped rather than received allows individuals to take responsibility for their projections, empowering them to co-create meaning in more adaptive, life-affirming ways.

5- Facilitate community-based somatic dialogue spaces where people share how they experience the world somatically and perceptually. Use somatic exercises to explore differences in felt reality and find common ground. Since culture shapes ontic projections, collective somatic work can be a tool for healing polarization and rebuilding a shared sense of reality at the community level.

Conclusion

Thomas Hanna’s 1981 article “Ontic Perception: A Function of Human Survival” was remarkably ahead of its time. Writing in an era when rotary phones and library card catalogs still defined daily life, Hanna anticipated a crisis of perception that would only become fully visible with the rise of digital technologies. At a time when personal computers were just entering the market and the Internet was limited to military and academic use, Hanna recognized that reality is not a fixed external truth but something constructed internally through the soma, our sensing and perceiving body.

In today’s hyper-connected world of algorithmic feeds, social media echo chambers, and digital disinformation, Hanna’s insight—that perception is actively shaped from within and closely tied to our physiological state—feels prophetic. While the technologies of 1981 had limited capacity to distort or fragment reality at scale, today's information ecosystems do so continuously and pervasively. Hanna foresaw that without awareness of how our bodies organize and project reality, we would become vulnerable to manipulation and fragmentation. His somatic philosophy anticipated many of the perceptual and epistemic challenges that now define life in the 21st-century digital age.

Now in this age of disinformation, the crisis we face is not merely about facts. It is about perception itself, and how our bodies tell us what is real. This truth crisis is profoundly somatic. When our perception is distorted, fragmented, or manipulated by external forces, our inner sense of coherence begins to break down. The result is anxiety, polarization, and a growing disconnection from both ourselves and others.

Thomas Hanna’s core insight is that reality is constructed from within. The soma gathers perceptual data from the external world, integrates it into its internal sense of self, and projects it back outward in a continuous sensory-motor feedback loop. The soma is always adapting to its environment and this adaptive capacity includes neuroplasticity and the ability to reorganize how we perceive and project reality. To navigate a fragmented digital world, we can consciously return to our own somatic experience. This is where coherence can be restored.

As Thomas Hanna reminds us:

““At this moment the reality that you and I experience is like an island in an ocean of possible realities... But this island of reality is our ground of support and the guarantor of our ongoing life. We must revere our island of reality, even as we must respect the surrounding ocean of possible realities.” ”

By honoring both our own somatic truth and the multiplicity of other possible realities, we might begin to heal the fractures of our time. We do this not by choosing one truth over another, but by living more consciously within the truth of our embodied experience.

References

Hanna, T. (1981). Ontic Perception: A Function of Human Survival. Somatics: Magazine-Journal of the Bodily Arts and Sciences, 3(2), 55-60.